Recently a colleague showed me an old publication he found while reorganizing his office. It was a book, not much more then a magazine really, called Film Sound Today, written by Larry Blake in 1984. It’s a collection of articles he had written for various publications about the sound processes behind the biggest Hollywood films of the time. Some of the films covered in depth are Return of the Jedi, Disney’s Fantasia re-release and Francis Ford Coppola’s One For The Heart. There is also an amazing article that covers the entire history of stereo film sound, from the first patents and blackboard concepts in the 1920s, up to what was taking the industry by storm in the last quarter of the century – Dolby Stereo.

I was familiar with Larry Blake because I had been reading his columns for years. When I was breaking into the the audio post industry in the ’90s my main source for shop talk in the the mass media was Mix Magazine. Although the magazine (then as now) covered music recording and live sound, it also had a regular column on film sound by Larry Blake. That column was the first thing I read when the magazine got delivered every month. I had no idea he had been writing about film sound for so long though.

Reading through Film Sound Today I am having blast exploring this cool archive of audio knowledge. Some of the concepts and equipment discussed seem so antiquated compared to what we have access to now. One passage discusses how Lucas Film is contemplating a new cutting-edge technology:

“The recently introduced Compact Disc is being considered to store Lucas Film’s extensive sound effects library. Instead of reels of 1/4 inch tape occupying a whole wall, the library could fit on one shelf crammed with about 100 compact discs. Thus sound editors at the facility will have the entire sound library at their finger tips.”

Another passage discusses how for Return of the Jedi they would be using a digital system called ASP (Audio Signal Processor) which was in the prototype stage. It is described as a “large special purpose computing device for digitized audio.” The hard drives for the ASP are 300 megabytes each and “the same size as a 24-track recorder.” Yikes!

Although some of the described equipment is distinctly from another time, many of the people interviewed are still vital to the industry to this day. There is a long section with Ben Burtt, discussing his process for creating all the different alien languages found in Return of the Jedi. He was in charge of dreaming up dialects for Jabba the Hut, the Ewoks and some of the six million other languages C3PO interprets fluently. Burtt’s basic premise was that the design of the fictional language had to be found in the source material, not in the processing and mixing stage.

“The general process is one of a very few number of tracks, with maximum effort in selecting the individual sounds and recording them in the first place. It is not a difficult mixing process, it is a difficult editing process.”

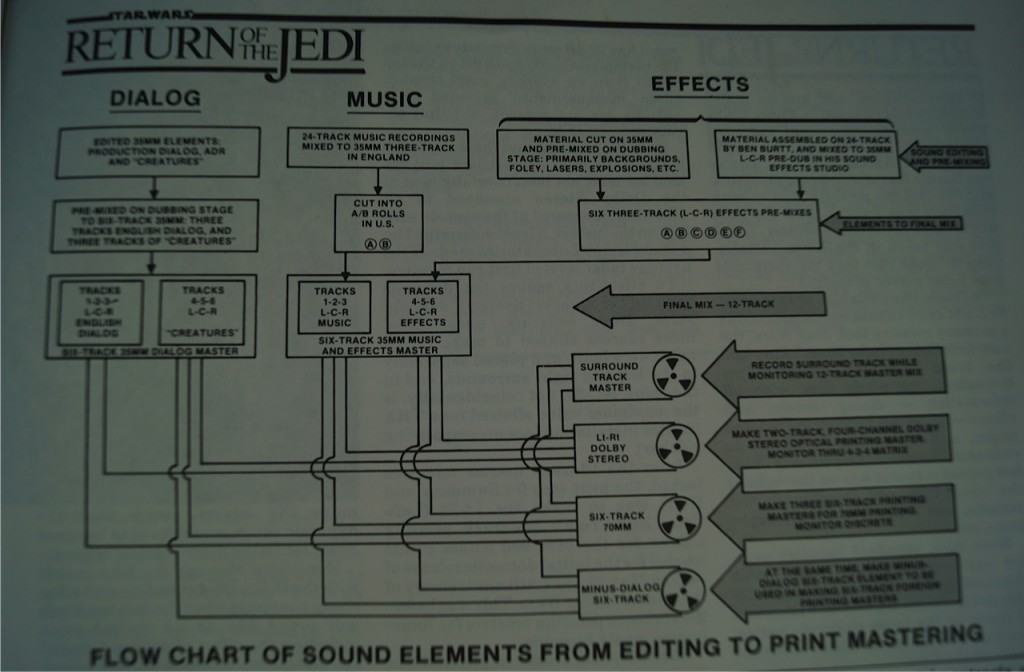

Other still-current industry heavyweights pop up as well. Randy Thom and Gary Summers were the re-recording mixers on Jedi, while the author of the important book Sound for Film and Television, Tom Holman, was the Lucas Film chief engineer. Walter Murch, Dale Strumpell and the late Alan Splet are also mentioned. The author himself went on to a storied film career as well; Blake was the re-recording mixer and supervising sound editor on almost twenty of Steven Soderbergh’s films, as well as many other movies.

On multiple occasions Blake refers to other impressive film sound tracks from the era, including the first two Star Wars films, The Black Stallion and Apocalypse Now. These are all considered classic films and important cinema sound touchstones to this day. One thing that surprised me is that the soundtrack to the film DragonSlayer is continually mentioned as being on par with these other classics. To be honest, I am completely in the dark about this film, and I don’t think I’m alone. This movie seems to have disappeared from our lexicon of noteworthy film sound achievements. Certainly the trailer makes it look like a somewhat forgettable film. I am going to try to track it down to hear for myself if its soundtrack still holds up against the iconic films it was once ranked alongside.

Larry Blake has always been a captivating writer. In Film Sound Today his writing style is less personal and opinionated than his later columns, but this book is still an interesting read. I would love to have him as a guest on the podcast one day. If anyone reading this has a way of contacting him please let us know.

I like to imagine someone stumbling onto the Tonebenders’ Dave Whitehead episode thirty years from now. I wonder how strange his words would seem to listeners that far in the future. Hopefully the state of the art will be so far advanced that they would be chuckling about the way we all do things now, and perhaps be inspired to uncover some brilliant soundtracks from the good old days.

[…] Timothy’s Blog on book about film sound in the 80s […]